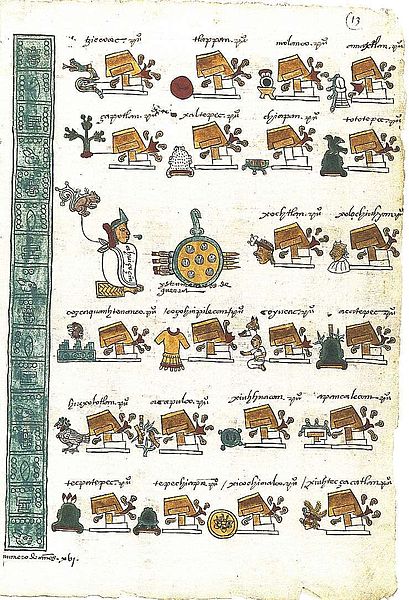

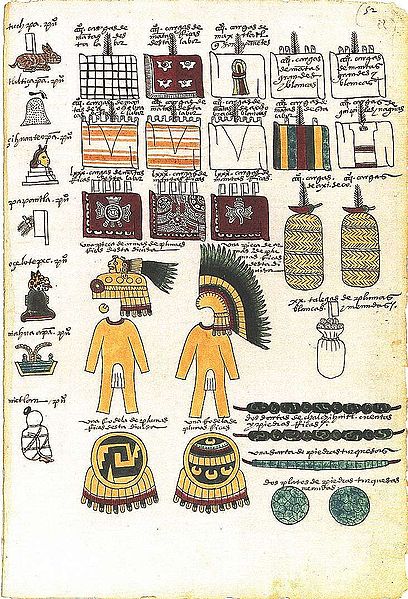

“The Codex Mendoza is an Aztec codex, created about twenty years after the Spanish conquest of Mexico with the intent that it be seen by Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain. It contains a history of the Aztec rulers and their conquests, a list of the tribute paid by the conquered, and a description of daily Aztec life, in traditional Aztec pictograms with Spanish explanations and commentary. It is named after Antonio de Mendoza, then the viceroy of New Spain, who may have commissioned it. After creation in Mexico City, it was sent by ship to Spain. The fleet, however, was attacked by French privateers, and the codex, along with the rest of the booty, was taken to France. There it came into the possession of André Thévet, cosmographer to King Henry II of France. Thévet wrote his name in five places on the codex, twice with the date 1553. It was later bought by the Englishman Richard Hakluyt for 20 French francs. Some time after 1616 it was passed to Samuel Purchase, then to his son, and then to John Selden. The codex was deposited into the Bodleian Library at Oxford University in 1659, 5 years after Selden’s death, where it remained in obscurity until 1831, when it was rediscovered by Viscount Kingsborough and brought to the attention of scholars.”

from Wikipedia and ThePublicDomainReview

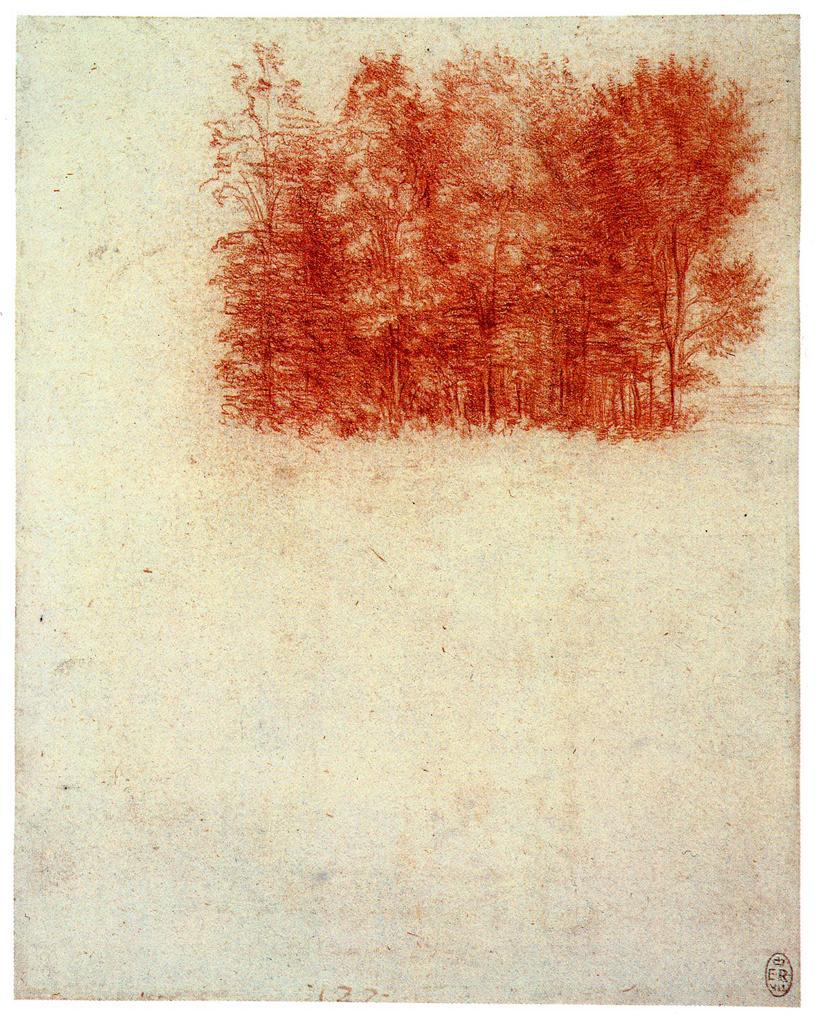

via Radimus