Comics

“Please apologize to your friend for me.”

“Likable characters are for weak-minded narcissists.”

Remembering 2000AD

“Can you imagine a time when your favourite comics creators and stories were published together in the same comic every week?”

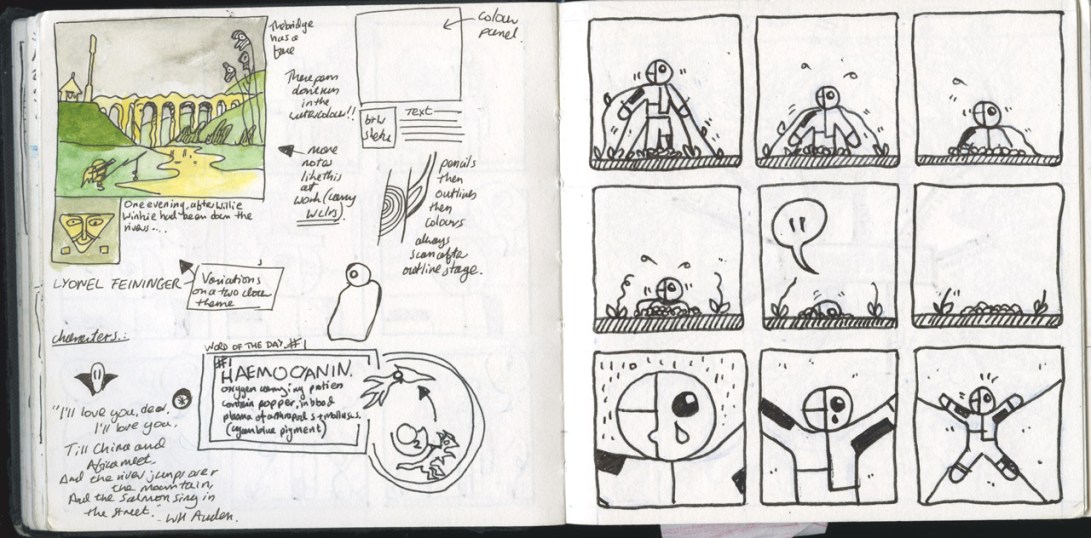

My Submission for Hourly Comics Day 2010

On Ditko and Abstraction

“The script is dominant, the story is what matters, images are subservient. This is what I would call–to borrow a term from deconstruction–the logocentric view of comics. “Logocentric” as centered upon the logos, which means not only “speech” or “discourse,” but also meaning, as in a verbalizable meaning.”

“Obviously, I’m a proponent of an anti-logocentric view of comics. Ditko and Kirby, in this view, only achieve their heights of artistry when they reverse that hierarchy, when the script becomes subservient to the art, rather than the reverse. Is this such a novel view of art? Not at all. As a matter of fact, the reversal has happened repeatedly in one of our most popular arts, or forms of entertainment, which most of the time is enjoyed precisely from this perspective: specifically, music.”

Notebook Pages

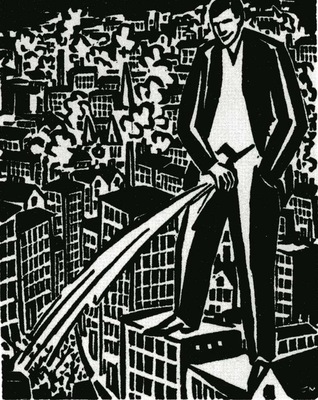

“Mon livre d’heures” by Frans Masereel (1919)

Frans Masereel (1919) Passionate Journey—arriving on the train

“Passionate Journey, or My Book of Hours (French: Mon livre d’heures), is a wordless novel of 1919 by Flemish artist Frans Masereel. The story is told in 167 captionless prints, and is the longest and best-selling of the wordless novels Masereel made. It tells of the experiences of an early 20th-century everyman in a modern city.”

Masereel’s medium is the woodcut, and the images are in an emotional, allegorical style inspired by Expressionism. The book followed Masereel’s first wordless novel, 25 Images of a Man’s Passion (1918); both were published in Switzerland, where Masereel spent much of World War I. German publisher Kurt Wolff released an inexpensive “people’s edition” of the book in Germany with an introduction by German novelist Thomas Mann, and the book went on to sell over 100,000 copies in Europe. Its success encouraged other publishers to print wordless novels, and the genre flourished in the interwar years.

“The story follows the life of a prototypical early 20th-century everyman after he enters a city. It is by turns comic and tragic: the man is rejected by a prostitute with whom he has fallen in love. He also takes trips to different locales around the world. In the end, the man leaves the city for the woods, raises his arms in praise of nature, and dies. His spirit rises from him, stomps on the heart of his dead body, and waves to the reader as it sets off across the universe.”

“Look at these powerful black-and-white figures, their features etched in light and shadow. You will be captivated from beginning to end: from the first pictured showing the train plunging through the dense smoke and bearing the hero toward life, to the very last picture showing the skeleton-faced figure among the stars. Has not this passionate journey had an incomparably deeper and purer impact on you than you have ever felt before?”

“‘ARCHITECTURE IS FROZEN MUSIC.’ (This is, I think, the aesthetic key to the development of cartoons as an art form.)”

“What you do with comics, essentially, is take pieces of experience and freeze them in time,” Ware says. “The moments are inert, lying there on the page in the same way that sheet music lies on the printed page. In music you breathe life into the composition by playing it. In comics you make the strip come alive by reading it, by experiencing it beat by beat as you would playing music…”