“I want to reveal what is usually kept hidden – it is no game – I tried to open peoples eyes to new realities: it is as true of the doll photographs as it is of Petit Traite de la Morale. The anagram is the key to my work. This allies me to the Surrealists and I am glad to be considered part of that movement, although I have less concern than some Surrealists with the subconscious, because my works are carefully thought out and controlled. If my work is found to scandalise, that is because for me the world is scandalous.”

sculpture

“Greenland’s Hand-Sized Wooden Maps Were Used for Storytelling, Not Navigation”

“For these seafaring people, geographic knowledge was something remembered and shared through stories and conversations of travels and hunting. “The drawing of charts and maps,” Holm wrote, “was of course quite unknown to the people of [Ammassalik], but I have often seen how clever they were as soon as they grasped the idea of our charts. A native from Sermelik, called Angmagainak, who had never had a pencil in his hand and had only once visited the East coast, drew a fine chart for me covering the whole distance from Tingmiarniut to Sermiligak, about 280 miles.” They also provided him with incredibly detailed descriptions of terrain, flora and fauna, and, in some cases, local weather patterns and lunar and solar cycles. To pass some of this knowledge on to the curious, acquisitive Holm, one hunter presented him with a set of unusual maps that have been, by turns, overlooked, discounted, misunderstood, and, eventually, admired.”

“But woodcarving was a common activity among the Tunumiit and Holm mentions that carving maps was not out of the ordinary. The Inuit people have used carvings in a certain way—to accompany stories and illustrate important information about people, places, and things. A wooden relief map, would have functioned as a storytelling device, like a drawing in the sand or snow, that could be discarded after the story was told. As geographer Robert Rundstum has noted, in Inuit tradition, the act of making a map was frequently much more important than the finished map itself. The real map always exists in one’s head. Though the maps themselves are unique, the sentiments and view of the world they represent were universal to the culture that made them.”

…Much more including annotated manipulatable 3-d models on this great post from Atlas Obscura.

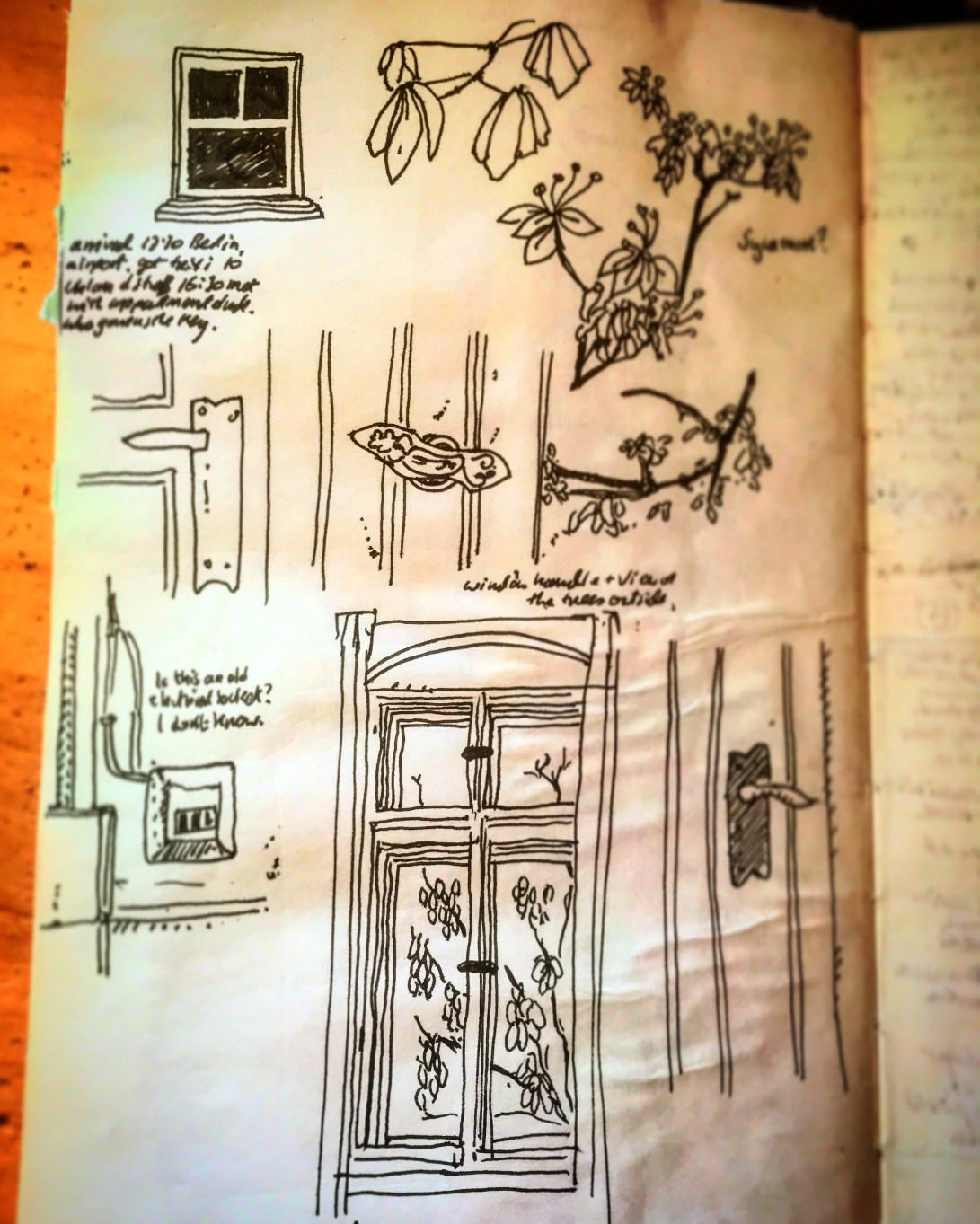

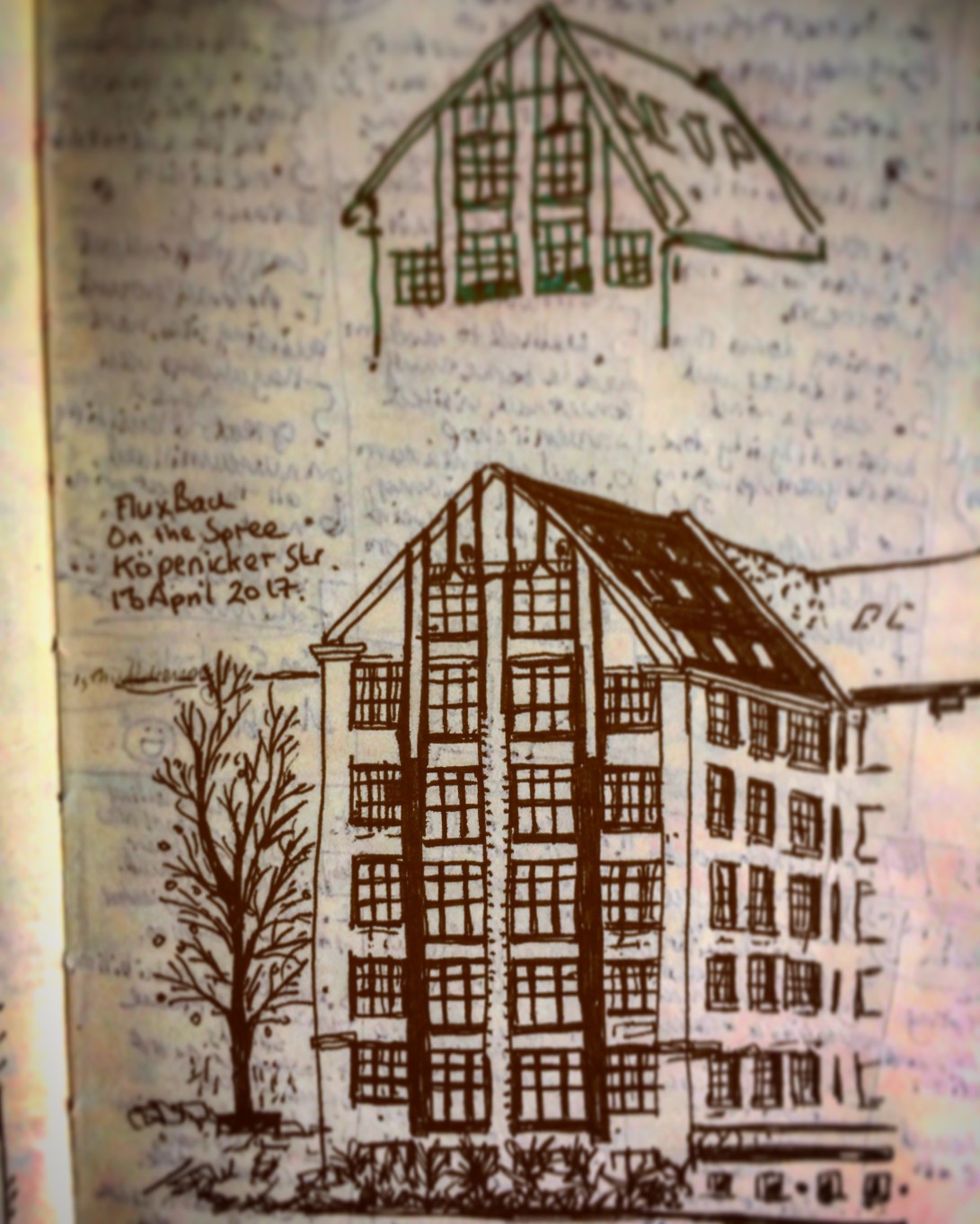

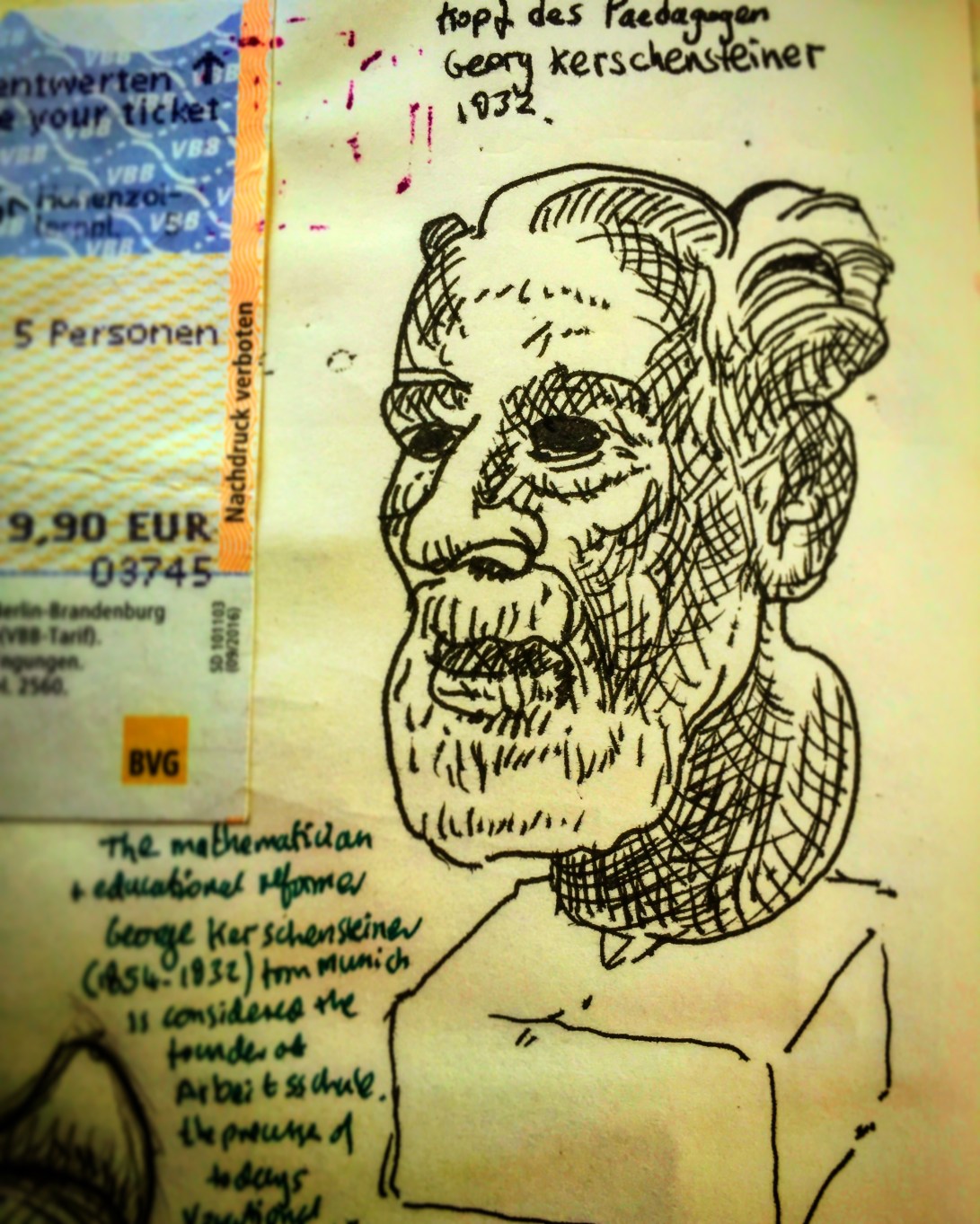

Spring trip to Berlin.

aka: Intermittently Regular #365 Sketch Project Update 172-182

It’s been a while so I am all out of sorts with drawings and order etc.

This is a batch from our Spring trip to Berlin. I have some more of these and I will post them in due course as some of them were scribbled on site and need a little bit of finishing off.

There’s some good advice here on drawing animals by Aaron Blaise, which could be applied to drawing from life of any kind. Mainly:

- Draw from Life

- Do your research before you go out.

- Bring the right supplies and be prepared.

- Observe first draw later.

- Keep it loose and make quick observations.

- Adjust revise your proportions as you go.

- Take lots of pictures and build your personal reference library.

You should definitely read the whole post here.

Anyways, back to Berlin:

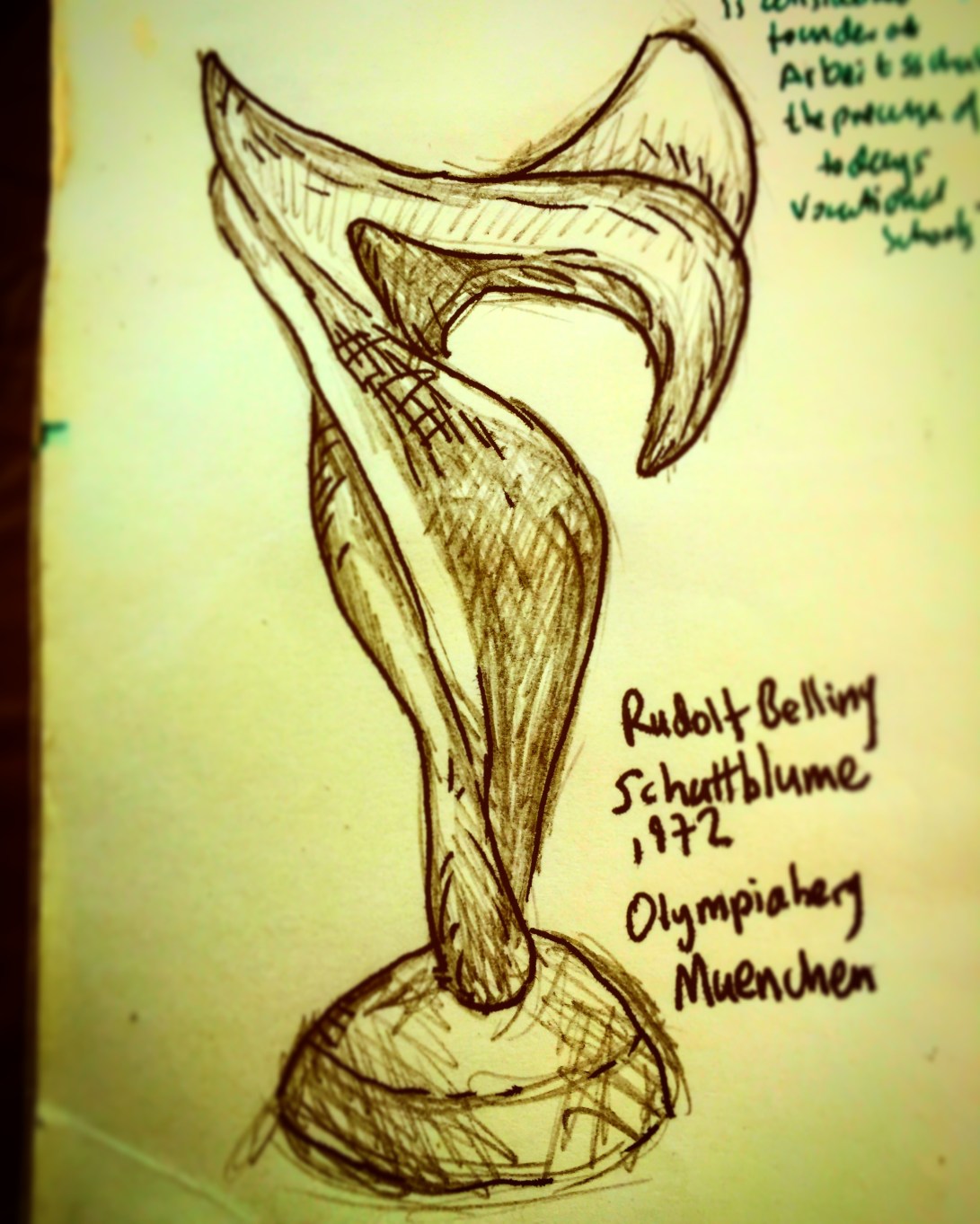

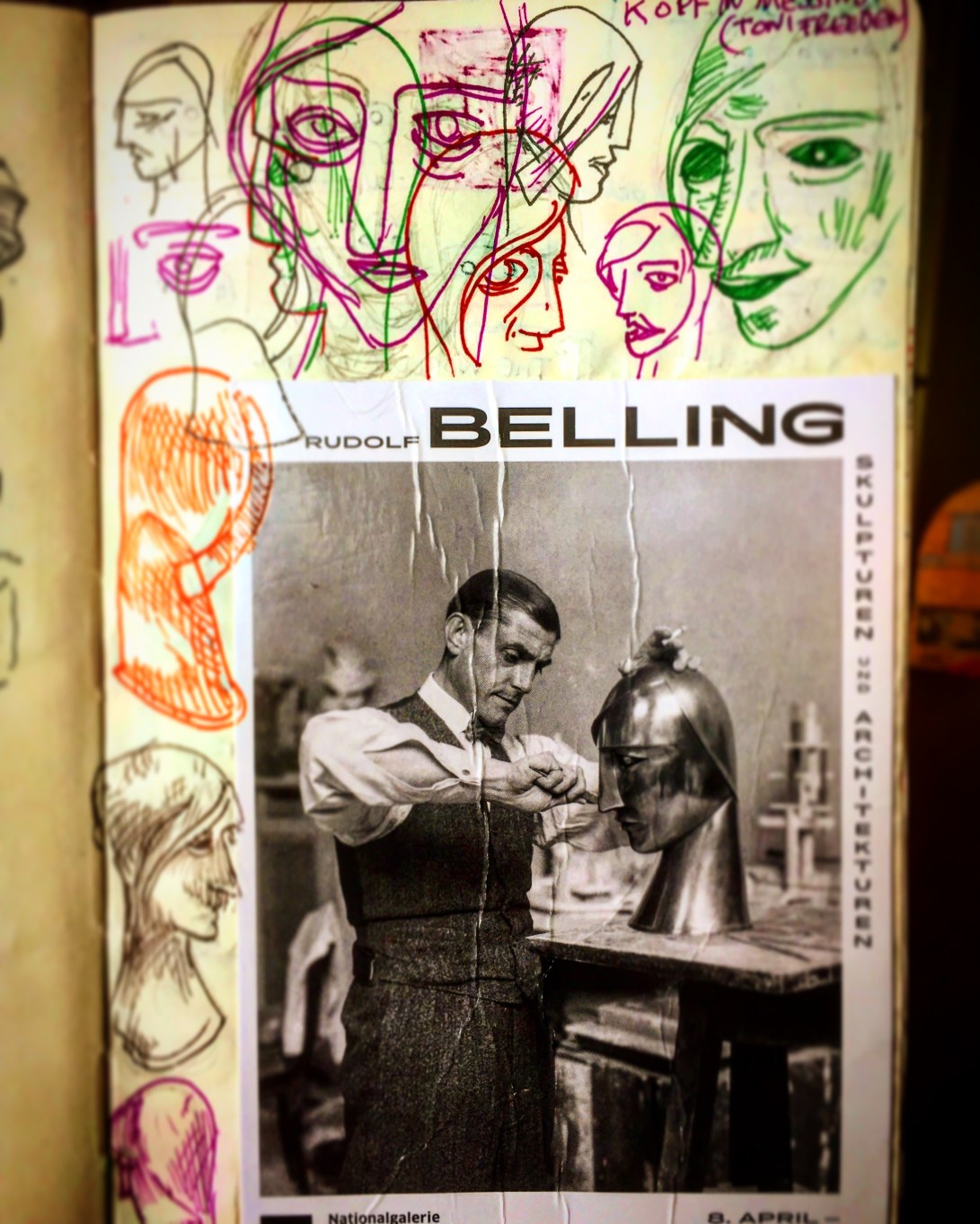

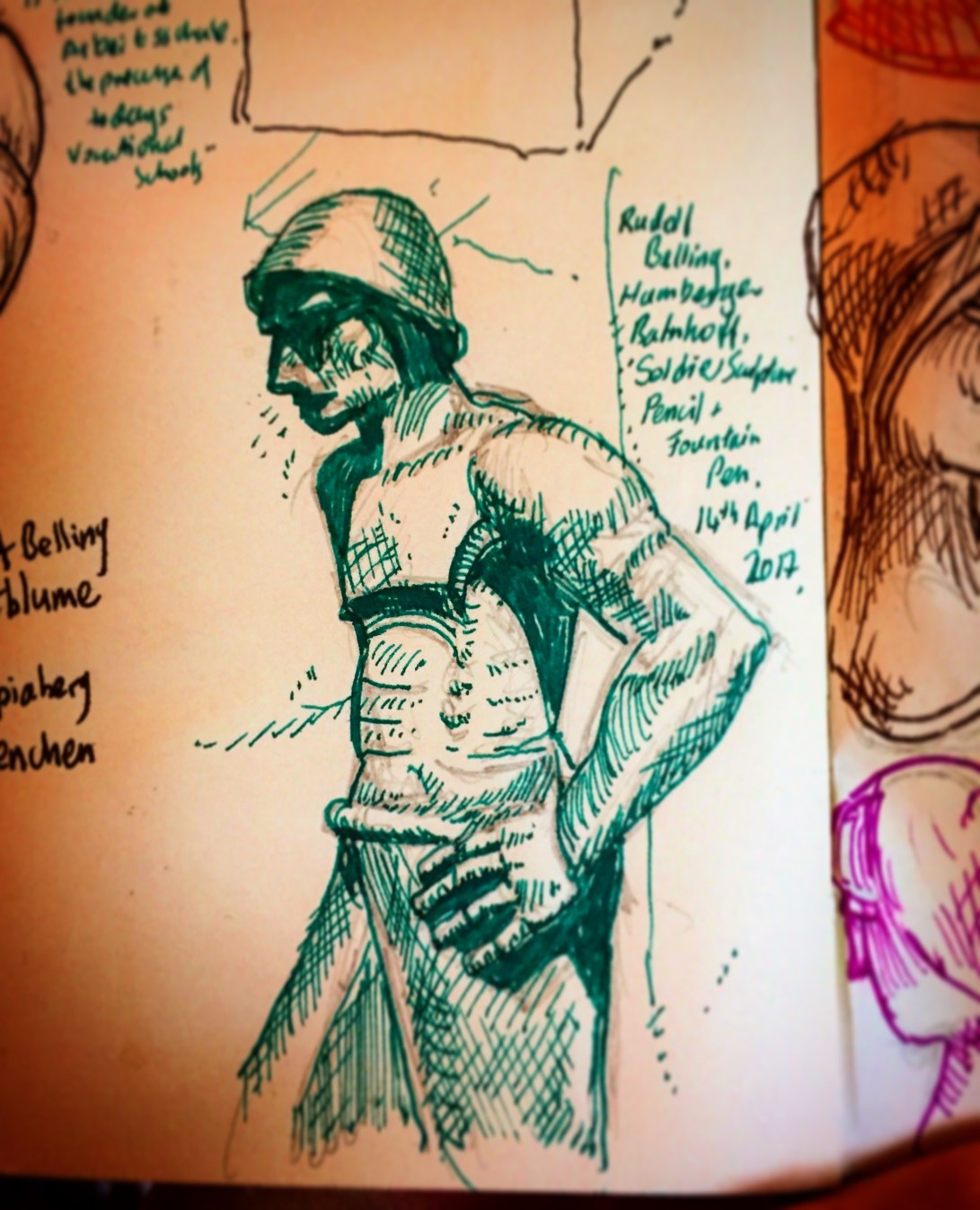

During out stay we were fortunate enough to visit the Rudolf Belling exhibition at the Hamberger Bahnhof museum. I was relatively unfamiliar with his work before this but we all really enjoyes seeing his work.

This from Wikipedia:

At the very beginning of the 20th century Rudolf Belling’s name was something like a battlecry. The composer of the “Dreiklang” (triad) evoked frequent and hefty discussions. He was the first, who took up again thoughts of the famous Italian sculptor Benvenuto Cellini (1500-1570), who, at his time, stated, that a sculpture should show several good views. These were the current assumptions at the turn of the century. However they foreshadow an indication of sculpture being three-dimensional.

Rudolf Belling amplified: a sculpture should show only good views. And so he became an opponent to one of the German head scientists of art in Berlin, Adolf von Hildebrandt, who, in his book, The problem of Form in Sculpture (1903) said: “Sculpture should be comprehensible – and should never force the observer to go round it”. Rudolf Belling disproved the current theories with his works.

His theories of space and form convinced even critics like Carl Einstein and Paul Westheim, and influenced generations of sculptors after him. It is just this point which isn’t evident enough today.

I hope to make a more comprehensive post about his work in the future.

Damien Hirst’s “Charity” begins it’s Twelve month stay at the RWA in Bristol.

Franz Xaver Messerschmidt (1736-1783)

“L’Inquietude” by Man Ray (1890-1976)

“One of Man Ray’s guiding principles was “to do the things that one is not supposed to do,” and here it seems he has used the camera to make a picture of something intangible, an emotion. Man Ray explored photography’s potential in the realm of abstraction, photographing a cloud of smoke gathering around a found-object sculpture in his New York studio. By manipulating his camera, he blurred the subject beyond recognition and created a sense of velocity and disequilibrium. The enigmatic title denies the existence of a recognizable subject in the photograph. Unknown to the viewer is the fact that Anxiety (L’Inquietude) is the name of the sculpture in the photograph, making this a craftily anti-documentary document of the three-dimensional piece.”

Karoo Ashevak

Karoo Ashevak, (Fantasy) Figure with Birds, 1972

Karoo Ashevak (1940 – October 19, 1974) was an Inuit sculptor who lived a nomadic hunting life in the Kitimeot, central Arctic region before moving into Spence Bay in 1960. His career as an artist started in 1968 by participating in a government-funded carving program. Working with the primary medium of fossilized whalebone, Ashevak created approximately 250 sculptures in his lifetime, and explored themes of shamanism and Inuit spirituality through playful depictions of human figures, shamans, spirits, and arctic wildlife