LITERATURES

Alternative Comics, Sequential visual narrative, photo stories, cave paintings. Little comics everywhere.

The Smithsonian Collection of Newspaper Comics edited by Bill Blackbeard

“As an undergraduate student and aspiring cartoonist, the book laid open most often on my drawing table was Blackbeard and Williams’ weighty Smithsonian Book of Newspaper Comics. For years I’d been led to believe by various comic book aficionados that the zenith of achievement for the medium were the EC comic books of the 1950s, but after discovering the Smithsonian book, it became all too clear to me that the real original geniuses of the medium were the pre-cinema cartoonists of the throwaway Sunday supplements of a half century prior. As a general history, the book evenly balanced a necessary all-inclusivity with an otherwise gently insistent esthetic sophistication, which was something of a virtuosic tightrope act of curation: covering everything while still allowing the greats to shine. Choosing a few representative examples of Krazy Kat and Little Nemo is hard enough, but what about introducing Gasoline Alley and Polly and Her Pals to a brand-new readership, to say nothing of uncovering the obscure efforts of George Luks and Lyonel Feininger? Even better, the strips were presented in a warm, large, full-color format which at the time must have been extraordinarily expensive, but allowed their complicated and intricate compositions to be truly re-appreciated; earlier histories of comics had tended towards text-clotted black-and-white tour schedules, amputating single panels and freeze-drying them in black and white as little more than passing souvenirs of an outmoded 19th and early 20th century naïveté. (As an aside, one of the deciding reasons I agreed to design the “Krazy and Ignatz” series was that Mr. Blackbeard was its acting editor, and I considered it a personal honor to be asked to contribute.) By devoting his life to the preservation and location of these near-extinct supplements and sections, Bill Blackbeard saved an American art from the certain peril of trash men, librarians and ultraviolet light so that we, the generations to come, could appreciate their unprepossessing, unpretentious and uproarious beauty. The comic strip may have been disposable, but Bill Blackbeard’s founding contribution to the understanding of it as an art was, and always will be, timeless.”

– Chris Ware

via Austin Kleon

“The idea of producing variations on a work from the past was probably inspired by Picasso who reinterpreted works by Grünewald, Delacroix, Manet, Gauguin and Velazquez himself.”

“Picasso is the reason why I paint. He is the father figure, who gave me the wish to paint……Picasso was the first person to produce figurative paintings which overturned the rules of appearance; he suggested appearance without using the usual codes, without respecting the representational truth of form, but using a breath of irrationality instead, to make representation stronger and more direct; so that form could pass directly from the eye to the stomach without going through the brain.”

1856 Burritt – Huntington Chart of Comets, Star Clusters, Galaxies, and Nebulae

“This rare chart of comets, star clusters and nebula was engraved W. G. Evans of New York for Burritt’s Atlas to Illustrate the Geography of the Heavens . Notes several important comets recorded in the previous 300 years including the Comet of 1689, the Comet of 1744, The Great Comet of 1680, the Great Comet of 1811, Halley’s Cement, the Great Comet of 119 and the Comet of 1843. Also shows several well known nebulas including the Horse Shoe Nebula, the Spiral Nebula and the Dumb Bell Nebula. This unusual chart appeared in the 1856 edition of Burritt’s Atlas and was not present in earlier edition.”

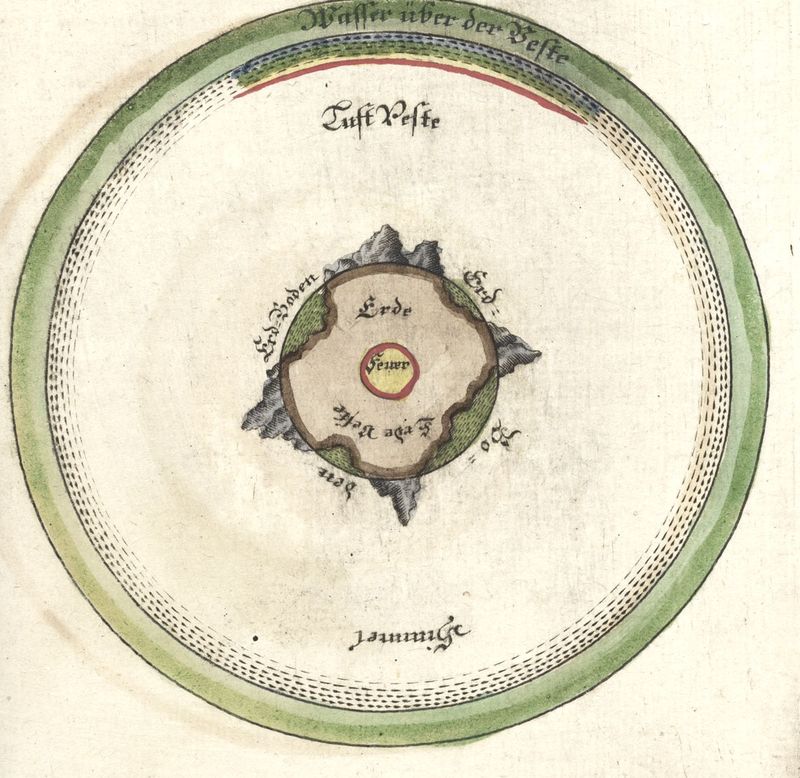

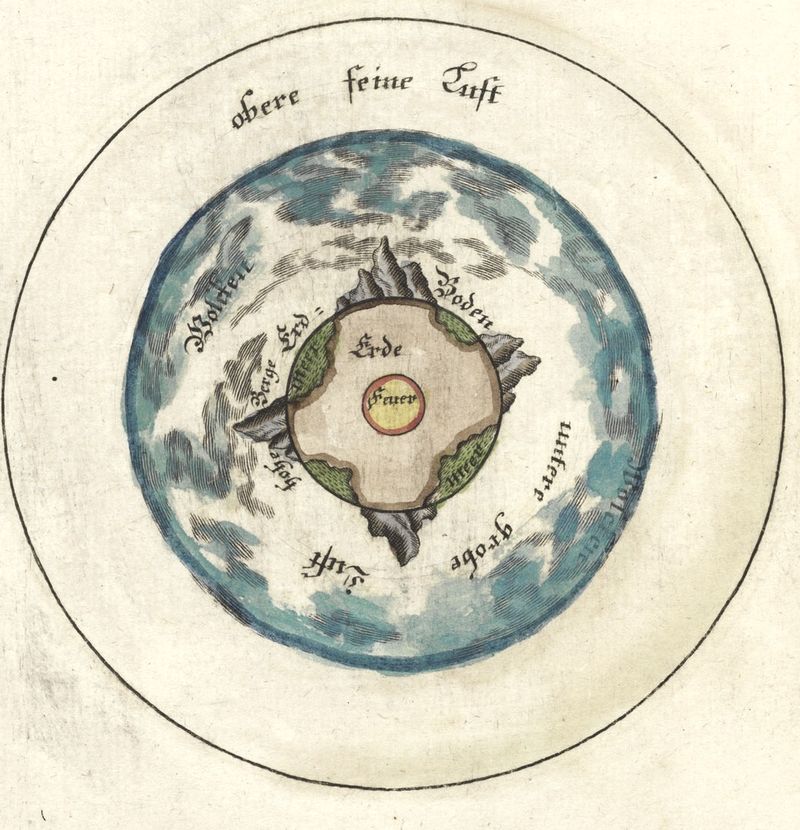

“Die Welt im Feuer, oder das wahre Vergehen und Ende der Welt, durch den letzten Sünd-Brand translate”

or: Depicting the destruction of the earth in several stages:

“This engraving is one of twelve found in a fine little book, the brainchild of clergyman/semi-scientist Jodocus Frisch (1714-1787), who delivered to the (un-) waiting world his vision of how the earth and heaven will come to an end, there at the end of days. Die Welt im Feuer, Oder das Wahre Vergehen und Ende der Welt, Durch den letzten Sünd-Brand (printed in Sorau by Gottlob Heboldm in 1746) is one of very few works that depict (in illustration) the destruction of the Earth, and even though Frisch illuminates biblically-based theory, the idea of the earth exploding into bits in primordial fire and so on was extraordinary. The images were done in four colors representing the four elements: yellow, brown, green and white represented (respectively) fire, earth, water and air. In this image, we see the fire-centric earth encircled by a sphere of water, which is surrounded by a sphere of fire, which in turn is surrounded by a sphere of air, with much bad stuff happening. “

More to be found at thesciencebookstore.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi (歌川国芳) (1797-1861)

A frieze of horses and rhinos near the Chauvet cave’s Megaloceros Gallery -300C

“During the Old Stone Age, between thirty-seven thousand and eleven thousand years ago, some of the most remarkable art ever conceived was etched or painted on the walls of caves in southern France and northern Spain. After a visit to Lascaux, in the Dordogne, which was discovered in 1940, Picasso reportedly said to his guide, “They’ve invented everything.” What those first artists invented was a language of signs for which there will never be a Rosetta stone; perspective, a technique that was not rediscovered until the Athenian Golden Age; and a bestiary of such vitality and finesse that, by the flicker of torchlight, the animals seem to surge from the walls, and move across them like figures in a magiclantern show (in that sense, the artists invented animation). They also thought up the grease lamp—a lump of fat, with a plant wick, placed in a hollow stone—to light their workplace; scaffolds to reach high places; the principles of stencilling and Pointillism; powdered colors, brushes, and stumping cloths; and, more to the point of Picasso’s insight, the very concept of an image. A true artist reimagines that concept with every blank canvas—but not from a void.”

DA VINCI’S BLOBS

Looking at a rapidly flowing stream or a thunderstorm leaves a strong visual impression, but many aspects of what is actually happening remain hidden from or are simply beyond the reach of observation, either by the naked eye or instruments. They have to be inferred from what can be observed, and this is a matter of interpretation, of imagination. It is very much the method Albert Einstein used in developing his theories of Relativity, because he could not directly observe objects moving close to the speed of light, or the movements of stars in interstellar space. In science it is called making a hypothesis, and the application of this method took modern physics far beyond empiricism (Newton had proudly claimed, “I make no hypotheses”), which was based strictly on what could be observed. Da Vinci, in this way as in others, anticipated future developments—he created hypothetical worlds that revealed the hidden structures of nature. These, in turn, helped him create paintings of great originality that are imbued with a lasting aura of conceptual power.

more here