reblogging johnfass

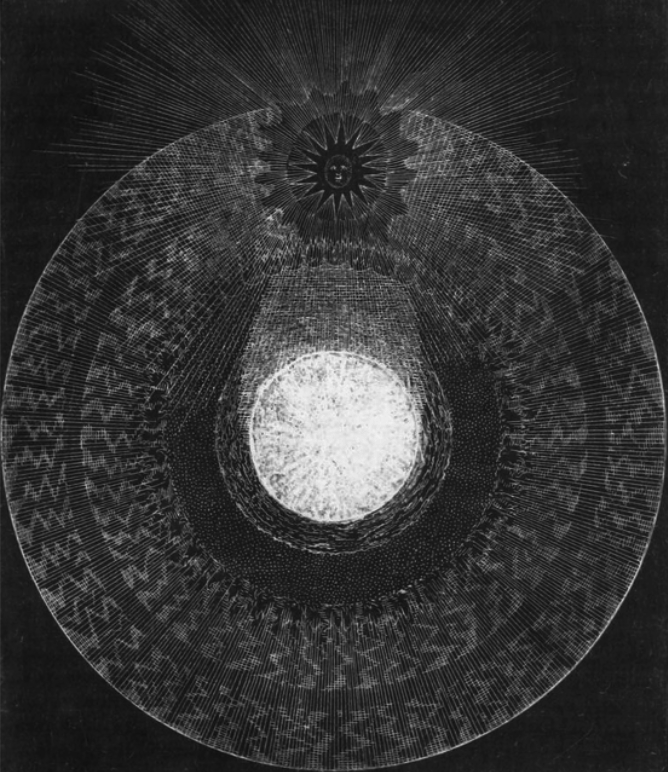

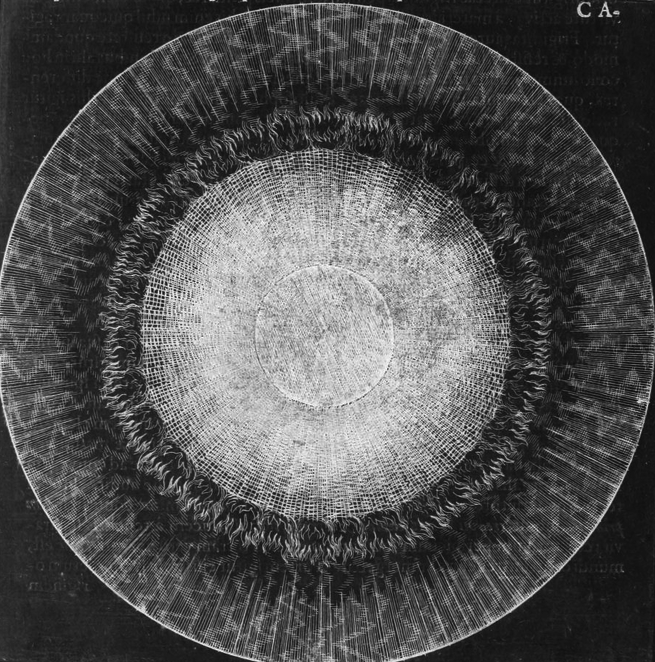

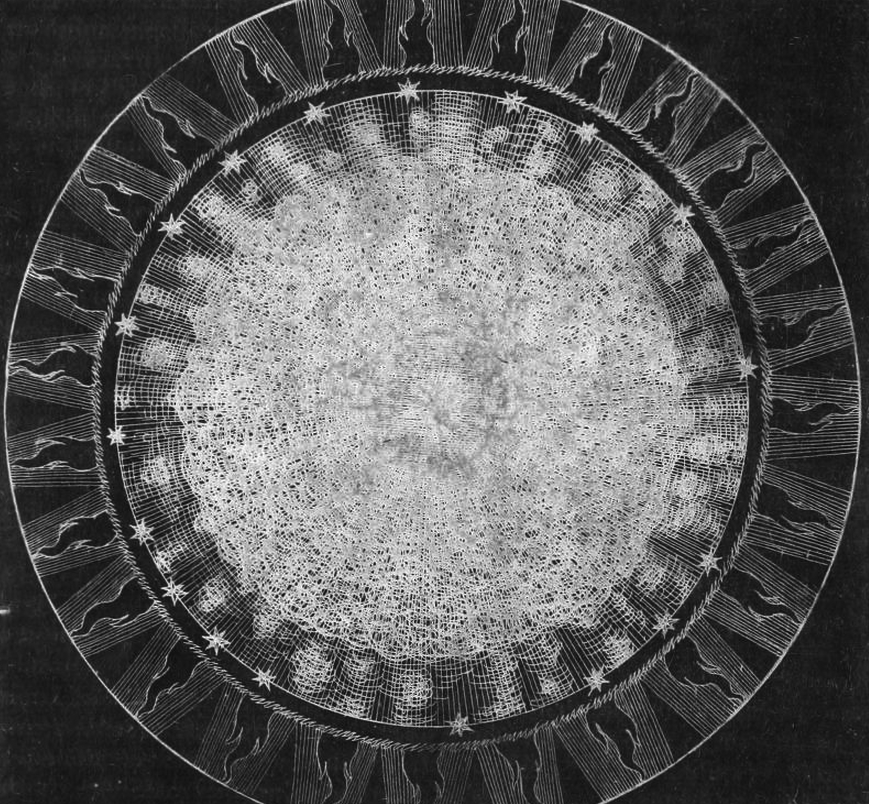

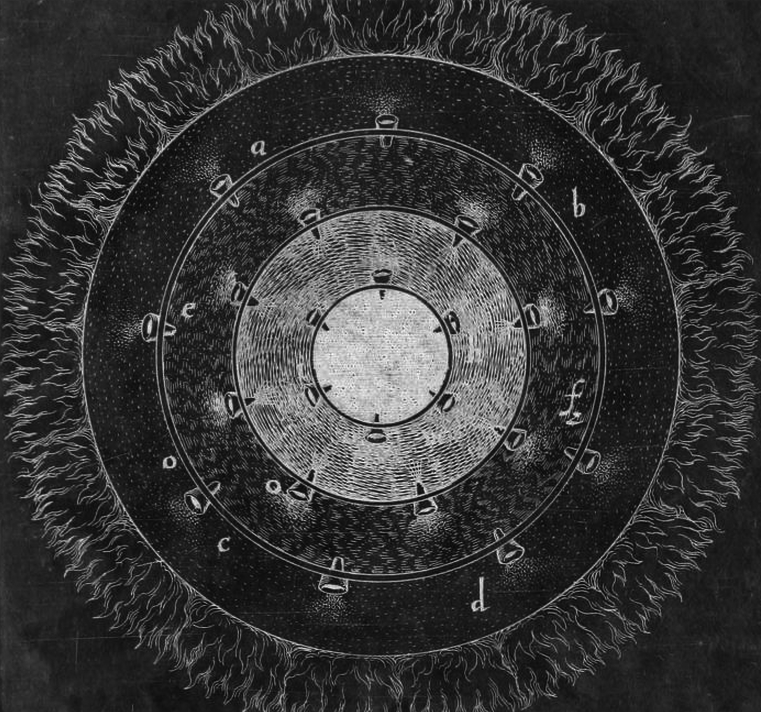

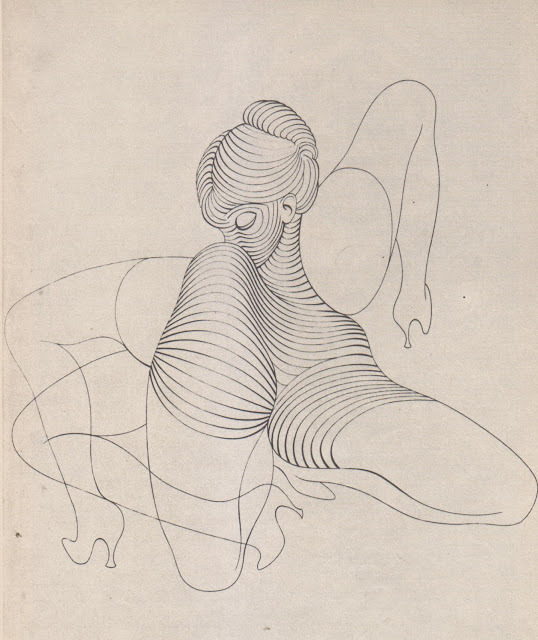

Currently working on a research project related to Canadian and Greenland Inuit with R0gMedia in Berlin. The diagram above is a genealogical diagram made in the mid 1950s by anthropologist Jean Malaurie, the first of its kind. It’s a hand made radial drawing, Malaurie has a whole series of them in his apartment in Paris, along with his extensive personal archive of research materials including photos, films, notebooks, drawings. While the broader aims of the project are to find an institution willing to host the collection, I’m trying to make an digital artefact out of this diagram that could bring the information alive and demonstrate how historical anthropological materials can be made relevant and contextualised for present and future generations. DIS2012 published a paper on this project for a workshop about slow technology. Slow technology DIS2012