“At the beginning of the twentieth century, Adolf Wölfli, a former farmhand and laborer, produced a monumental, 25,000-page illustrated narrative in Waldau, a mental asylum near Bern, Switzerland. Through a complex web of texts, drawings, collages and musical compositions, Wölfli constructed a new history of his childhood and a glorious future with its own personal mythology. The French Surrealist André Breton described his work as “one of the three or four most important oeuveres of the twentieth century”. Since 1975, our aim is to make Adolf Wölfli’s work known through one-man and group exhibitions as well as publications.”

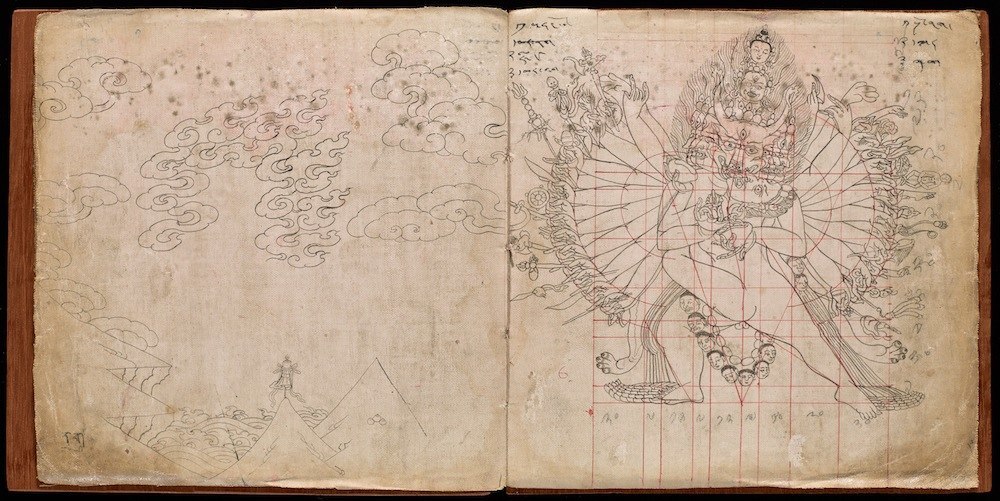

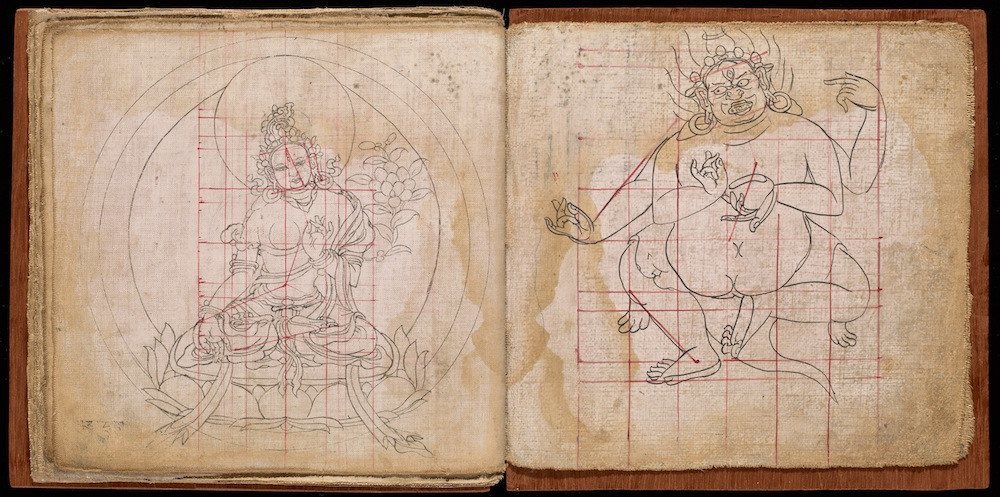

“Wölfli’s first epic From the Cradle to the Grave runs over 2,970 pages of text and 752 illustrations bound by Wölfli into nine books. It takes the form of a travelogue whose principal hero is a boy called Doufi (a nickname for Adolf). Together with his family, Doufi travels all over the world which is, in the name of progress, duly explored and inventorised. In From the Cradle to the Grave, Wölfli transforms his miserable childhood into a glamorous story of wonderful adventures, discoveries and awesome hazards, all of which are famously overcome. The text, which mixes prose with poetry and extensive lists, is accompanied by colourful maps, portraits and illustrations of events such as combats, collapses and catastrophes. In these drawings one first encounters the form of the “Vögeli“ – a little bird which can be understood as the protector of the ubiquitous Wölfli’s alter ego and simultaneously as a sexual symbol filling in any potential empty space”

“Adolf Wölfli. From the Cradle to the Grave. Bedlam=Walking Wheel, Provisional Map of Both the Kingdom of Spain and Portugal, Dromedary Indian and Vosel Stubborn Donkey Mask, Lea Tantaria, Condor Eggs, Hall of Blacks, London South, Map of the Two Principalities Sonoricije and the West Bzimbzabazaru, Helvetic Cathedral in Northern Amazonian Hall, Atlantic Ocean Waves and Přístaf Cradle Lisbon (top to bottom). 1912.”

“Wölfli’s imaginary autobiography and one-person utopia starts with „From the Cradle to the Grave“ (1908-1912). In 3,000 pages, Wölfli turns his dramatic and miserable childhood into a magnificent travelog. He relates how as a child named Doufi, he traveled „more or less around the entire world,“ accompanied by the „Swiss Hunters and Nature Explorers Taveling Society.“ The narrative is lavishly illustrated with drawings of fictitious maps, portraits, palaces, cellars, churches, kings, queens, snakes, speaking plants, etc.”

“In the second part of the writings, the „Geographic and Algebraic Books“, Wölfli describes how to build the future „Saint Adolf-Giant-Creation“: a huge „capital fortune“ will allow to purchase, rename, urbanize, and appropriate the planet and finally the entire cosmos. In 1916 this narrative reaches a climax as Wölfli dubs himself St. Adolf II.”

“Jean Dubuffet, the French artist and founder of „Art Brut,“ called Wölfli „le grand Wölfli,“ the Surrealist André Breton considered his oeuvre „one of the three of four most important works of the twentieth century,“ and the Swiss curator Harald Szeemann showed a number of his pieces in 1972 at „documenta 5,“ the renown contemporary art exhibition in Kassel, Germany. Wölfli’s writings, which he considered his actual life’s work, only began to be systematically examined and transcribed in 1975 when the Adolf Wölfli Foundation was founded. Elka Spoerri (1924-2002) built up the Adolf Wölfli Foundation and was its curator from 1975 to 1996.”

“Every Monday morning Wölfli is given a new pencil and two large sheets of unprinted newsprint. The pencil is used up in two days; then he has to make do with the stubs he has saved or with whatever he can beg off someone else. He often writes with pieces only five to seven millimetres long and even with the broken-off points of lead, which he handles deftly, holding them between his fingernails. He carefully collects packing paper and any other paper he can get from the guards and patients in his area; otherwise he would run out of paper before the next Sunday night. At Christmas the house gives him a box of coloured pencils, which lasts him two or three weeks at the most.”

— Walter Morgenthaler, a doctor at the Waldau Clinic,

“Naturally enough, the question whether Wölfli’s music can be played is asked again and again. The answer is yes, with some difficulty. Parts of the musical manuscripts of 1913 were analyzed in 1976 by Kjell Keller and Peter Streif and were performed. These are dances – as Wölfli indicates – waltzes, mazurkas, and polkas similar in their melody to folk music. How Wölfli acquired his knowledge of music and its signs and terms is not clear. He heard singing in the village church. Perhaps he himself sang along. There he could see song books from the eighteenth century with six-line staffs (explaining, perhaps, his continuous use of six lines in his musical notations). At festivities he heard dance music, and on military occasions he heard the marches he loved so well. More important than the concrete evaluation of his music notations is Wölfli’s concept of viewing and designing his whole oeuvre as a big musical composition. The basic element underlying his compositions and his whole oeuvre is rhythm. Rhythm pervades not only his music but his poems and prose, and there is also a distinctive rhythmic flow in his handwriting.””

“After Wölfli died at Waldau in 1930 his works were taken to the Museum of the Waldau Clinic in Bern. Later the Adolf Wölfli Foundation was formed to preserve his art for future generations. Its collection is now on display at the Museum of Fine Arts in Bern.”

Information via Magic Transistor, Wikipedia and Adolf Wölfli Foundation.