Notebook: Ethel

Notebook: Ethel

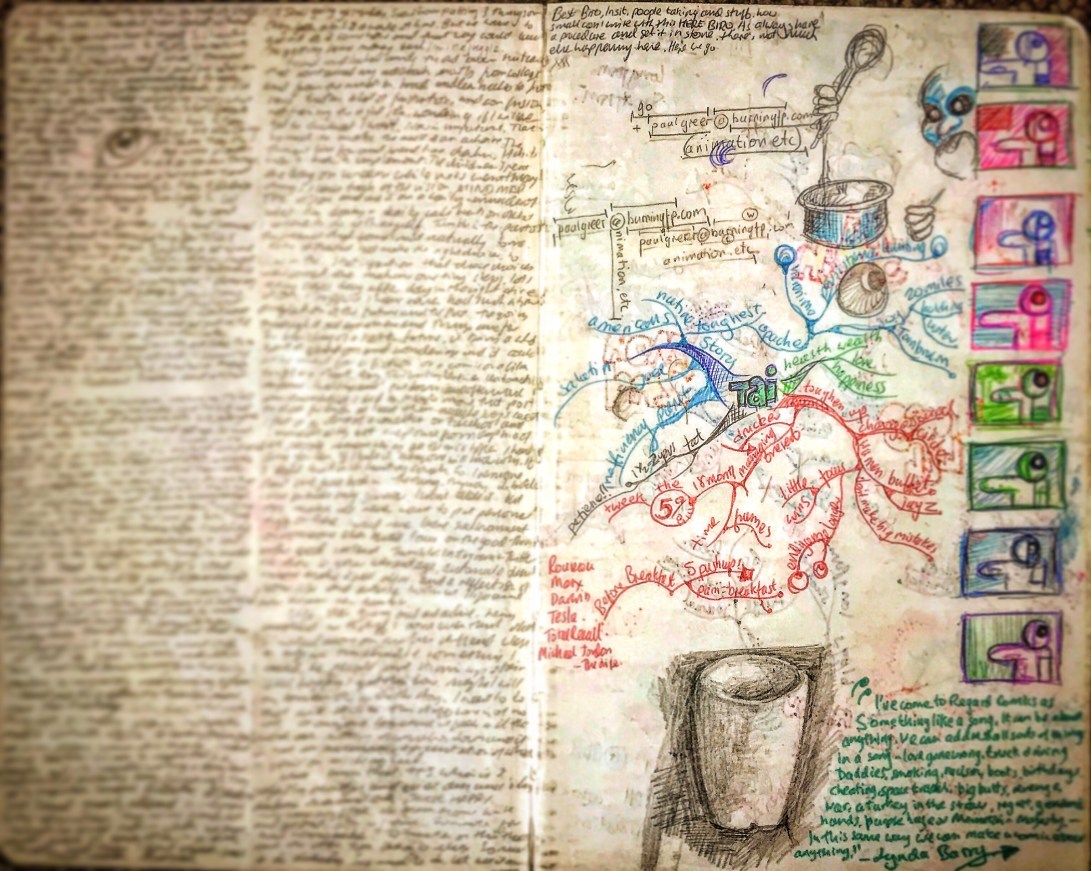

Spread 2.

First drafts, mug drawing, rough mind map, comics and a quote from Lynda Barry.

It’s along the lines of:

“I’ve come to regard comics as something like a song. It can be about anything. We can address all sorts of things in a song, love gone wrong, truck driving, Daddies, smoking, boots, birthdays, cheating, space travel, big butts, revenge, war, a turkey in the straw, regret, genders, hands, purple haze . We can this way we can make comics about anything.”

– Although I did write it down in a hurry!